Opulence is just the beginning of this design star's legacy.

Estate of Karen Radkai

Ifirst became aware of the work of French

designer Henri Samuel in the mid-1980s, in what might be called his

robber baron phase. At that heady time in American social history there

were a few decorators from England and Europe working in New York for

very visible clients: Geoffrey Bennison had just performed miracles for

Guy and Marie-Hélène de Rothschild on East 66th Street, and Henri

Samuel and his project for Susan and John Gutfreund at 834 Fifth Avenue

were the talk of the town.

Before then the apotheosis of Reagan-era classical

style had been basically Georgian. Afterward a gap was bridged, and it

was said that Samuel’s work didn’t just evoke the past, it was as good

as anything in that past. Samuel delivered to the New World something

that was thought to be no longer possible: the authentic opulence of

another continent and another time.

Later I learned the missing pieces of

the Samuel story. This happened, as it often does, in the form of an

auction catalog. The Christie’s Monaco sale after his death in 1996

contained many avant-garde works of contemporary “art furniture,” as

well as pictures of his Paris apartment that were positively bohemian—

luxurious, yes, but very artistic. You must remember that this was

before that apartment was well known, and images were not just waiting

for you on the internet. One had to research, save magazines, connect

dots. It was a revelation how Samuel had lived at home, with

contemporary art and zany furniture, and it was hard to square this with

his work for the second Gilded Age.

Emily Evans Eerdmans’s new Rizzoli book, Henri Samuel: Master of the French Interior($75),

is a long time coming. Samuel’s reputation has been growing steadily,

and it’s amazing there has been no book until now. Which Samuel will you

like best? There is one for every era. He worked in many styles, but

what he stood for consistently was quality. Jacques Grange, who worked

for Samuel early in his career and wrote the foreword, described to me

an office environment that was very formal and hierarchical. But, he

added with great respect, “that is where I learned what quality is.”

Excerpted

here are passages that explore Samuel’s influence on younger designers

today; his collaborations with such artists as Balthus, Philippe

Hiquily, and Guy de Rougemont; and his work for American plutocrats like

the Gutfreunds (on Fifth Avenue) and Jerry Perenchio (in the house made

famous by the title sequence of The Beverly Hillbillies). If

you like what you see (and have had a good year), both properties are,

coincidentally and for the first time in decades, now for sale. But

start with the book.

An excerpt from Henri Samuel: Master of the French Interior by Emily Evans Eerdmans

Henri

Samuel mixed the contemporary with the classical to thrilling effect.

Throughout his career the decorator proclaimed there was no “Samuel

style” but that each project evolved from the client’s taste. “I

remember seeing images in the 1990s, in a Christie’s auction catalog, of

Henri Samuel’s iconoclastic Paris apartment,” says Delphine Krakoff of

Pamplemousse Design in New York City.

Like Samuel she often pairs a classically

articulated room with experimental pieces, so that it looks as if it has

been furnished over time. “It was filled with artwork and furniture by

Balthus, Atlan, César, and Hiquily, combined with cutting-edge

contemporary as well as neoclassical design. I was taken by his

unexpected and fearless commitment to a unique vision, his understanding

of history and of design and architecture, without being constrained by

it. History is just a point of departure in his design process.”

In 1970, after 25 years as head of the design firm Alavoine, Samuel began a new chapter in his career: Henri Samuel, décorateur.

He opened his own firm, prompted not by ambition or a desire to have

his name at the forefront but because Alavoine had finally closed its

doors. At 66 the designer was internationally acclaimed as a master of

French decoration, and kings of both countries and industry clamored for

his time. Samuel set up shop on the ground floor of his apartment

building at 83 Quai d’Orsay and maintained a small staff to oversee all

projects.

In addition to Madame Chaminade, his secretary, and

Jacqueline Lallemand, his accountant, there were Jacques Cayron and a

Monsieur Hanché, who were his design associates. There was also a

full-time draftsman. When Samuel moved to 118 Rue Faubourg

Saint-Honoré, around 1976, the staff worked out of a small office in

his apartment, where a minuscule stairway led up to a drawing studio.

“Pierre,

a tiny man who drew incredibly in the style of Louis XV, Louis XVI, and

Empire, drafted the plans for everyone,” recalled the architect

Christian Magot-Cuvrû, who began working with Samuel in the early

1980s. The work was intense, but the office was run with civility.

Every

day Samuel would have lunch at Maxim’s or Le Relais at the Plaza

Athénée, often dining with friends such as the Duchess of Windsor.

“Tea-time at Monsieur Samuel’s was very important. Around 4:30 p.m. his

majordomo would come to serve us tea, and it was during this moment of

pleasant relaxation when we spoke of everything and nothing for 30

minutes,” Magot-Cuvrû remembers.

Working with such a prominent clientele called for absolute discretion. David Linker, a master ébéniste,

recalls that at the famous Cour de Varenne furniture restoration

workshop—where he worked exclusively on Samuel projects—one had to be

invited to purchase the important 18th-century items that passed through

the workshop, and it was understood that should the buyer want to

resell, he would do it through the Cour de Varenne. In this way

important, often royal, pieces could be tracked and their restoration

never compromised. When Linker or his colleagues helped deliver a piece

to a residence, they were never told the owner’s identity.

Samuel

patronized the same artisans repeatedly, so that they essentially

became an extension of his team and knew his preferences intimately. He

was very specific about color and was always on site to supervise the

mixing of colors, which could take hours before he was satisfied.

Laurence du Plessix, who worked in Samuel’s office from 1984 to ’87,

remembers Samuel’s dissatisfaction with a carpet that was too bright;

the decorator added dust to make it more subdued. If a molding wasn’t

exactly what he wanted, Samuel would have it remade, even at his own

expense.

Thanks to his having restored the

Rothschilds’ famed Château de Ferrières in the 1950s, and having

worked at Versailles, Samuel was firmly established as a master of the

historical interior, as well as one of the most adept interpreters of le goût Rothschild,

which is what drew clients including Sisley founders Hubert and

Isabelle d’Ornano, Valentino Garavani, and other major Parisian

magnate-collectors to hire him, even as he started to be very much in

demand in the United States.

In postwar America the “Louis Louis” look became de

rigueur among a certain high society set. By 1962 the fashion for

French design was so pronounced that decorator Billy Baldwin dubbed it

FFF (“Fine French Furniture”). This craze brought a branch of Maxim’s to

Chicago in December 1963; the opening included a Dior fashion show. To

faithfully reproduce the restaurant’s Belle Epoque interiors, the owners

sought out Henri Samuel.

Samuel was working

steadily in the U.S. by the 1960s. Jayne Wrightsman, one of New York’s

most distinguished proponents of FFF, began working with Samuel

following the retirement of her longtime decorator, Stéphane Boudin of

Jansen. Samuel’s later collaboration on the Wrightsman Galleries at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art secured his position as one of the world’s

most eminent interior designers, and his relationship with Wrightsman

would lead, years later, to one of his most notable projects: the

Gutfreund residence.

The 1980s in New York were a heady time of

maximalist extravagance stoked by the roar of Wall Street. When Salomon

Brothers CEO John Gutfreund and his wife Susan moved to 834 Fifth Avenue

in 1987, the residence’s Henri Samuel interiors made a splash. Women’s Wear Daily

reported, “It’s the talk of New York, and one of those lucky few who

have sneaked a peek at Susan and John Gutfreund’s apartment says it is

the ‘most lavish and beautifully opulent’ home in the city, a place that

truly has the atmosphere of a house and not just a flat.”

Susan

had been introduced to Samuel by Wrightsman and soon became a cherished

client and pupil of the decorator. Samuel even guided the Gutfreunds in

their choice of domicile. He counseled against an Italianate townhouse

in favor of the 20-room apartment on the seventh and eighth floors of

834 Fifth, which was designed in 1929 by Rosario Candela. He

particularly approved of the large windows, which offered spectacular

views, even to seated guests, of Central Park.

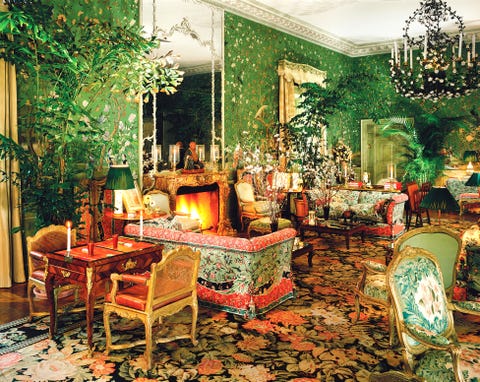

Antiques purchased during the Gutfreunds’ travels

in Europe inspired the decoration of the winter garden room, which was

flooded by too much natural light to be the library, as originally

planned. Gilt trelliswork paneling made of resin gave the room both

order and fantasy.

With the assistance of

architect Thierry Despont, Samuel knocked out walls to create a

50-foot-long living room, laid the floors with parquet de Versailles,

and uncovered windows in the stairway to let more light in. Susan

remembered, “Henri would sit and stand in the room, observing the color

from all angles, in the bright morning light as well as in the

afternoon. He studied it by lamplight... He always came himself, never

sending an assistant. He was like a couturier, always fine-tuning

details.”

The dining room was furnished with a

suite of 18th-century white and Wedgwood-blue Adam-style furniture from

Jayne Wrightsman. The curtain design was also 18th-century, the pink

under-curtain fabric having been a gift to Susan from Karl Lagerfeld.

“Henri gave you the perfect base, like a couture dress that was sheer

perfection whether you added jewels or not,” says Susan, who is now an

interior designer in her own right.

After

visiting the Gutfreunds’ apartment, entertainment mogul Jerry Perenchio

decided Samuel was the ideal person to restore the property he had just

acquired in Los Angeles. The house’s exterior was famous for its use on

the 1960s television show The Beverly Hillbillies. Designed by

architect Sumner Spaulding for Lynn Atkinson, who was the engineer of

Boulder Dam and who loved the Louis XV style, the limestone-clad

reinforced concrete residence, which featured a 150-foot-tall indoor

waterfall and a pipe organ, had taken five years to build. When the

house was finished in 1938, Atkinson’s wife Berenice took one look and

asked, “Who would ever live in a house like this?” The house sat empty

until it was sold in 1947 to Arnold Kirkeby, whose family sold the house

to Perenchio in ’86. Over time Perenchio added three contiguous lots to

the estate, which now amounts to 10 acres.

Perenchio agreed to Samuel’s demand that

everything, even the slope of the roof, had to be redone in order to

achieve a “proper representation of an 18th-century château.” Over the

next five years the house was gutted, rebuilt, and decorated. Before the

south façade was rebuilt, a crew of 26 painted a full-size

trompe-l’oeil version of the elevation for the Perenchios to approve. To

find limestone that matched the original, Samuel and the Perenchios

flew by helicopter from quarry to quarry in France and then hired a

local couple to live on site to ensure that it was cut properly.

The entrance hall was transformed with a new

staircase and a floor of limestone and black marble. The front and

interior wooden doors were replaced with glass ones, so that what had

been a dark space became a light-filled, welcoming one. The domed

plaster ceiling of the Morning Room proved to be one of the most

ambitious architectural features. Made in France in one piece, the

ceiling was too large to fit through the eight door of a 747—so it was

cut into sections for transport and reassembled on site.

In November 1991 the Perenchios finally moved in.

“It was a wonderful adventure and one of the greatest learning

experiences of our lives,” Jerry said, “as this extraordinary artist

taught us and guided us for five years in the realization of our dream.”

Henri

Samuel’s name is almost unknown to younger generations of American

designers. Brian J. McCarthy, who opened his New York office after years

of working for the esteemed Parish-Hadley, is one exception. “There’s

an order and structure to classical French rooms, and while Henri would

bring that order to them, there would be something that would shake it

and break it, and make it youthful,” he says. “There’s something so

smart about the way he decorated; it’s beyond timeless. If you recreated

one of Henri’s rooms, it would look as fresh today as it did then. To

me that speaks volumes about how great he was. He was a genius, pure and

simple.”

No comments:

Post a Comment